Can Dogs Control Their Tails? Expert Insight Into Canine Tail Movement

If you’ve ever watched your dog’s tail wag independently of their body language, you might wonder: are they doing that on purpose? The truth is more nuanced than a simple yes or no. Dogs have remarkable voluntary control over their tails, but this control works differently than human limb movement. Their tails serve multiple purposes—from balance and communication to emotional expression—and dogs can manipulate them with surprising precision.

Understanding tail control in dogs reveals fascinating insights into canine neurology, behavior, and communication. Whether your pup is signaling joy, anxiety, or curiosity, their tail tells a story that goes beyond what meets the eye. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the science behind tail movement, what different tail positions mean, and how injuries or conditions can affect this important body part.

Anatomy of the Canine Tail

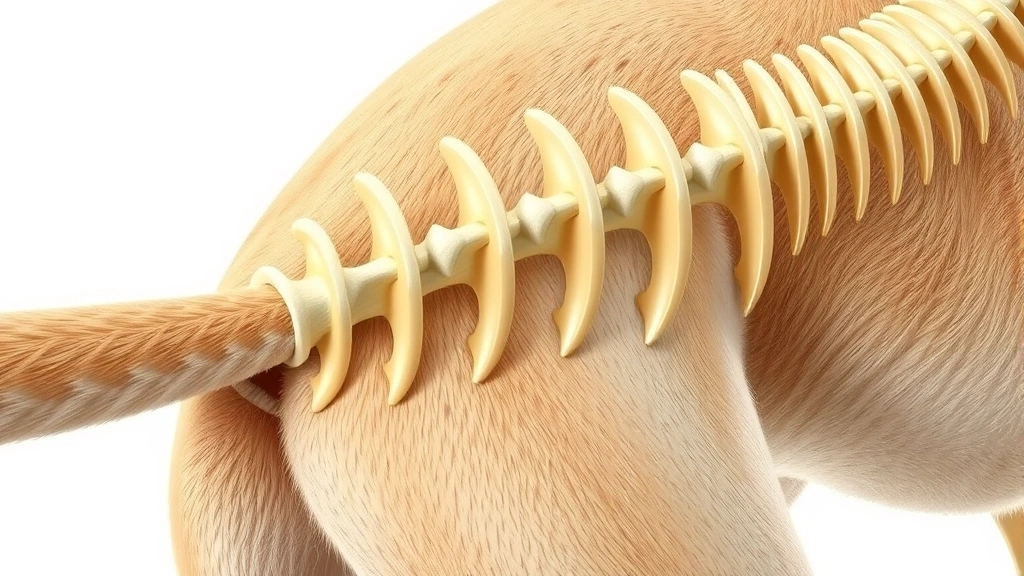

A dog’s tail is far more complex than it appears. The canine tail contains approximately 20-23 vertebrae (called caudal vertebrae), which is roughly one-fifth of the total vertebrae in a dog’s spine. These vertebrae are connected by muscles, ligaments, and tendons that allow for an impressive range of motion. The tail also contains numerous nerves that provide sensory feedback to the brain about the tail’s position and movement.

Unlike human fingers or arms, which are controlled by muscles in the forearm and upper arm, tail movement is primarily controlled by intrinsic muscles—muscles located within the tail itself—and extrinsic muscles that originate from the spine and pelvis. This unique arrangement allows dogs to move their tails in almost any direction: up, down, side to side, in circles, and even in figure-eight patterns.

The vertebral structure of the tail provides both flexibility and support. Each caudal vertebra is smaller than those in the lower spine, which contributes to the tail’s increased mobility. Blood vessels and nerves run through the center of these vertebrae, making the tail a sensitive and highly innervated body part. This extensive nerve network means dogs receive constant feedback about their tail’s position, even without looking at it.

Different dog breeds have different tail characteristics. Some breeds have naturally curled tails (like Pugs and Akitas), while others have long, whip-like tails (like Greyhounds). Some breeds have docked tails or naturally short tails, but regardless of the tail’s shape or size, the underlying anatomical structure remains remarkably similar across all dog breeds.

Voluntary vs. Involuntary Tail Movement

Dogs absolutely can control their tails—but not always. The answer involves understanding the difference between voluntary and involuntary movements. Voluntary tail movements are those the dog consciously decides to make, while involuntary movements happen automatically in response to emotional or physiological stimuli.

Voluntary Tail Control

Dogs demonstrate clear voluntary tail control in many situations. They can deliberately wag their tails when greeting their owners, adjust their tail position when navigating tight spaces, and even use their tails for balance when turning sharply during play or exercise. Studies have shown that dogs can modulate their tail wagging speed and amplitude based on the context—wagging faster when excited and slower when cautious.

Puppies learn to control their tails gradually, much like human babies learn to control their limbs. Young puppies have less precise tail control, but as their nervous system develops and they gain experience, they become increasingly skilled at manipulating their tails intentionally. By adulthood, most dogs have mastered sophisticated tail control that allows them to communicate complex emotional states.

Involuntary Tail Movement

However, not all tail movement is voluntary. When a dog is startled or frightened, their tail may tuck between their legs automatically—this is a reflexive response controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Similarly, when a dog is extremely excited or happy, their tail may wag uncontrollably despite the dog’s attempts to remain still. This involuntary component of tail movement is tied directly to emotional states and happens without conscious deliberation.

Research published by animal behavior scientists indicates that tail position and movement are influenced by a dog’s emotional state at a neurochemical level. Dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters affect both the dog’s emotional experience and their physical tail positioning. This means a dog’s tail position often reflects their genuine emotional state, making it a reliable indicator of how they’re feeling.

Tail Communication and Body Language

A dog’s tail is perhaps their most expressive communication tool. While many people focus on tail wagging as a sign of happiness, the reality is considerably more nuanced. Tail position, speed of wagging, height, and stiffness all convey different messages.

Tail Height and Position

The height at which a dog holds their tail communicates a great deal about their confidence and emotional state. A tail held high and straight typically indicates confidence, alertness, or dominance. A tail held at mid-level usually suggests a calm, neutral emotional state. A tail tucked between the hind legs indicates fear, anxiety, or submission. The specific angle and how tightly the tail is tucked can reveal just how frightened or anxious the dog is feeling.

Interestingly, research has shown that dogs can interpret other dogs’ tail positions. Studies conducted at the American Animal Hospital Association and various veterinary behavioral journals demonstrate that dogs respond differently to other dogs displaying high-held versus low-held tails, indicating they understand the communicative significance of tail position.

Wagging Patterns and Meaning

The direction and speed of tail wagging also matter. A fast, broad wag typically indicates happiness and excitement. A slow, stiff wag might suggest uncertainty or wariness. Some research has even found that dogs wag their tails more to the right when they’re feeling positive emotions and more to the left when experiencing negative emotions—a phenomenon related to how the brain’s hemispheres control different sides of the body.

Contrary to popular belief, a wagging tail doesn’t always mean a friendly dog. A stiff, high-held tail wagging quickly can indicate aggression or high arousal. Context is crucial—the entire body language of the dog, including ear position, facial expression, and body posture, must be considered alongside tail movement to accurately interpret what the dog is communicating.

Tail Control and Emotional States

The connection between tail control and emotional states reveals the intimate link between a dog’s physiology and psychology. When a dog experiences strong emotions, their ability to control their tail voluntarily becomes compromised or enhanced depending on the emotion.

Excitement and Joy

When dogs are genuinely happy and excited, their tail control becomes almost involuntary—they simply cannot help but wag their tails vigorously. This uncontrollable wagging demonstrates that the emotional centers of the brain are overriding the motor cortex’s usual precise control mechanisms. It’s similar to how humans smile involuntarily when experiencing genuine happiness. A dog’s entire hindquarters may move side to side along with the tail when they’re experiencing extreme joy.

Fear and Anxiety

Conversely, when a dog is frightened or anxious, they typically lose the ability to hold their tail high and proud. Fear triggers the sympathetic nervous system, which causes the tail to tuck automatically. This response is so deeply ingrained that most dogs cannot override it through conscious effort, even if trained to do so. The tucked tail position reduces the dog’s visual profile, which may have evolutionary advantages by making them appear smaller and less threatening to potential threats.

Confidence and Calm

Dogs in a calm, confident state typically demonstrate excellent voluntary tail control. They can adjust their tail position deliberately to suit the situation—raising it when greeting a friend, lowering it slightly in the presence of an authority figure, or holding it at a neutral angle when simply going about their day. This flexibility in tail positioning demonstrates sophisticated motor control and emotional regulation.

Understanding your dog’s emotional state through their tail can help you respond appropriately to their needs. If you notice your dog’s tail is consistently tucked or held in an unusual position, it might indicate stress, anxiety, or a health issue that warrants attention from your veterinarian.

Health Issues Affecting Tail Control

Several medical conditions can impair a dog’s ability to control their tail. Understanding these conditions is important for recognizing when your dog needs veterinary care.

Tail Injuries and Fractures

Dogs can fracture or injure their tails through accidents, rough play, or being stepped on. A tail fracture typically results in loss of control over the portion of the tail beyond the fracture point. The dog may hold the tail at an unusual angle or be unable to move the distal (end) portion. Most tail fractures heal well with rest and pain management, though some severe cases may require surgical intervention.

Nerve Damage

Damage to the nerves controlling the tail can result from spinal injuries, severe trauma, or certain neurological conditions. This can manifest as partial or complete loss of tail control. In some cases, nerve damage is temporary and resolves as the nerves heal. In other cases, the damage may be permanent, requiring the dog to adapt to life with reduced or absent tail mobility.

Degenerative Myelopathy and Other Spinal Conditions

Progressive spinal diseases like degenerative myelopathy can gradually affect tail control as the condition progresses. These diseases damage the nerves in the spinal cord, leading to progressive loss of function. Dogs with spinal arthritis may also experience reduced tail mobility and control due to pain and inflammation.

According to resources from the ASPCA, regular veterinary check-ups can help identify spinal and neurological issues early. If you notice sudden changes in your dog’s tail control or positioning, contact your veterinarian promptly for evaluation.

Anal Gland Issues

Problems with anal glands can cause dogs to hold their tails at unusual angles or tuck them excessively. Dogs with anal gland discomfort or infection may lose interest in normal tail movement and spend more time licking or nibbling at the base of their tail. This is a common but often overlooked cause of altered tail behavior.

Behavioral Responses to Health Issues

Sometimes dogs lose voluntary tail control due to pain or discomfort unrelated to the tail itself. A dog experiencing abdominal pain, hip dysplasia, or other orthopedic issues might hold their tail differently as an unconscious response to managing pain. Similarly, a dog experiencing neurological issues might display abnormal tail positioning or involuntary tail movements.

It’s worth noting that while nutritional factors and diet don’t directly affect tail control, a healthy diet supporting joint and neurological health is important for maintaining overall mobility. Ensuring your dog has proper nutrition—including appropriate amounts of omega-3 fatty acids for neural health and balanced proteins for muscle maintenance—supports healthy tail function.

If your dog’s tail control changes suddenly or progressively worsens, schedule a veterinary appointment. Your vet can perform neurological exams and imaging if necessary to identify any underlying conditions. Early intervention often leads to better outcomes for many tail-related health issues.

FAQ

Can dogs wag their tails on command?

Most dogs cannot reliably wag their tails on command in the way they can sit or lie down. While some highly trained dogs might learn to wag on cue, tail wagging is primarily an involuntary emotional response. However, dogs can learn to control their overall body position, which might result in more tail wagging in certain contexts. The emotional component of tail wagging makes it difficult to train as a traditional obedience command.

Why do some dogs wag their tails more than others?

Individual differences in tail wagging frequency relate to personality, breed tendencies, and emotional reactivity. Some dogs are naturally more expressive and enthusiastic, while others are more reserved. Breed genetics also play a role—some breeds have been selected for more animated behavior and expression. Additionally, a dog’s early socialization and life experiences influence how readily they display tail wagging behavior.

Is a wagging tail always a sign of a friendly dog?

No. While a loose, broad wag at mid-to-high tail height usually indicates friendliness, a stiff, high-held tail wagging quickly can indicate aggression or high arousal. Similarly, a tail tucked between the legs indicates fear or anxiety. Always assess the entire dog’s body language—ear position, facial expression, body posture, and the context of the situation—before assuming a wagging tail means the dog is friendly.

Can tail docking affect a dog’s ability to communicate?

Yes, tail docking does affect canine communication. Dogs with docked tails have a reduced ability to express themselves through tail movement and positioning. They cannot achieve the same range of tail positions or communicate as effectively with other dogs. This is one reason many animal welfare organizations oppose routine tail docking for cosmetic purposes. Dogs with naturally short or curled tails adapt their communication style, but they have less flexibility in tail expression compared to dogs with full-length tails.

What should I do if my dog loses tail control?

If your dog suddenly loses the ability to control their tail or shows significant changes in tail positioning and movement, contact your veterinarian. This could indicate injury, nerve damage, spinal issues, or other medical conditions requiring professional evaluation. Describe the changes you’ve observed and when they started. Your vet may perform a physical examination and possibly recommend imaging or other diagnostic tests to identify the underlying cause.

Do all dog breeds have the same tail control abilities?

While all dog breeds have similar underlying anatomical structures for tail control, some breeds may have different functional abilities based on their tail structure. Dogs with naturally curled or short tails might have a more limited range of motion compared to dogs with long, straight tails. However, the fundamental ability to control their tails voluntarily exists across all breeds. Breed-specific tail shapes don’t prevent dogs from using their tails for balance, communication, and emotional expression.

How does a dog’s age affect tail control?

Puppies gradually develop tail control as their nervous system matures and they gain motor coordination. Young puppies display less precise tail control than adult dogs. As dogs age into their senior years, degenerative conditions like arthritis or spinal degeneration might affect tail mobility and control. However, most adult dogs in their prime maintain excellent voluntary and involuntary tail control throughout their lives.