Ever wonder why your dog can twist mid-air to land on their feet, or how they manage those impossible yoga poses on the couch? It all comes down to the dog skeleton—a marvel of evolutionary engineering that’s way more flexible and complex than ours. Understanding canine bone structure isn’t just trivia for vet students; it helps you recognize when something’s wrong, prevent injuries, and appreciate just how athletic your furry friend really is.

The dog skeleton is built for speed, agility, and survival. Unlike humans, dogs have 319 bones (compared to our measly 206), and their spines are incredibly mobile. This anatomical advantage is why your pup can chase squirrels with such explosive power and why they seem to have a spine made of rubber when they’re stretching.

Basic Structure of the Dog Skeleton

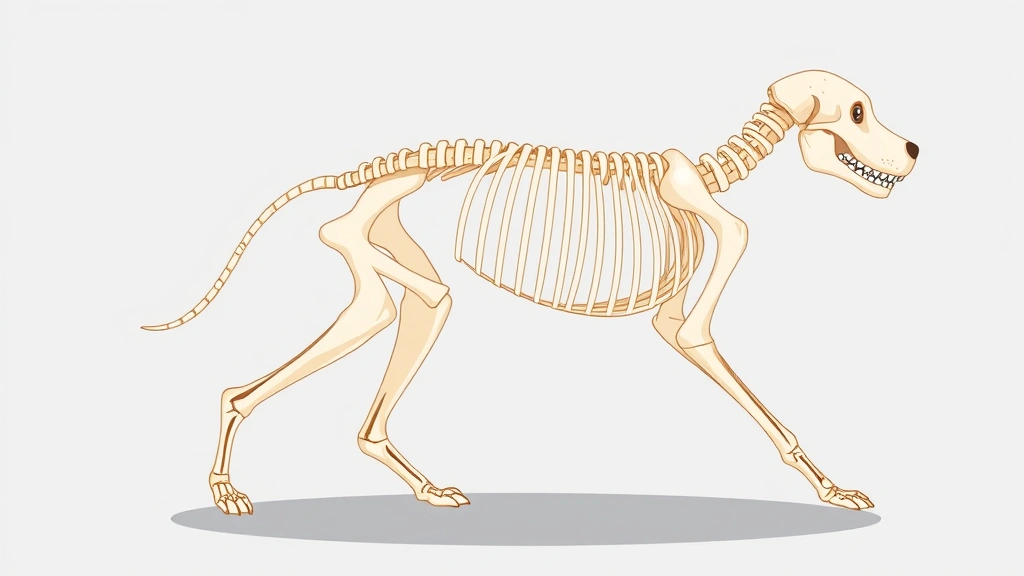

The dog skeleton is divided into two main systems: the axial skeleton (skull, spine, and ribcage) and the appendicular skeleton (limbs, shoulders, and pelvis). Think of it like a building—the axial skeleton is the frame and support beams, while the appendicular skeleton is the scaffolding that lets your dog move around.

Dogs have significantly more bones than humans, and here’s why: they have extra vertebrae in their spine (especially in the lumbar region), and their tails contain a whole separate string of bones called caudal vertebrae. That’s right—your dog can control their tail because it has its own skeletal structure with muscles attached.

The bones themselves are living tissue, constantly remodeling and adapting to stress and activity. When your dog runs, plays, or even sleeps in the same position repeatedly, their bones respond by becoming stronger or, in some cases, developing problems.

Pro Tip: A dog’s skeleton reaches full maturity around 12-18 months, depending on breed size. Large breed dogs take longer to fully ossify (harden) than small breeds, which is why you shouldn’t over-exercise giant breed puppies.

Understanding the basic structure helps explain why certain breeds are prone to specific issues. A Dachshund’s long spine makes them vulnerable to intervertebral disc disease (IVDD), while a German Shepherd’s hip angle puts them at risk for dysplasia.

The Spine and Vertebrae: Flexibility Central

Your dog’s spine is like a flexible cable made of 53 vertebrae, divided into five regions: cervical (neck), thoracic (chest), lumbar (lower back), sacral (pelvis), and caudal (tail). This incredible flexibility is what allows dogs to turn their heads nearly 270 degrees and twist their bodies in ways that defy physics.

Each vertebra is separated by intervertebral discs—think of them as tiny shock absorbers made of cartilage and gel. These discs are crucial for spinal health, and when they degenerate or rupture, you get IVDD (Intervertebral Disc Disease), which can range from mild pain to complete paralysis.

The thoracic spine is fused to the ribcage, creating a protective cage for the heart and lungs. The lumbar spine, on the other hand, is incredibly flexible—this is where many spinal injuries occur because dogs use this region for twisting, jumping, and sudden directional changes.

Here’s something most people don’t realize: the dog skeleton’s spinal design is optimized for forward motion and lateral (side-to-side) movement, but not for vertical loading like climbing stairs repeatedly or jumping off high furniture. This is why senior dogs often develop arthritis in their spines—years of impact and twisting take their toll.

The sacral vertebrae are fused together and connect the spine to the pelvis, providing stability during running and jumping. Damage to this region is rare but serious, as it affects hind limb function.

Safety Warning: Avoid repetitive jumping, especially in young large-breed dogs. Their growth plates (epiphyseal plates) don’t fully close until 12-18 months, and excessive impact can cause permanent joint damage.

Limbs and Paws: Built for Movement

The dog skeleton’s limbs are a study in efficiency. Dogs are digitigrade walkers, meaning they walk on their toes (digits) rather than flat-footed like humans. This gives them a longer stride and faster acceleration—perfect for hunting, herding, or chasing that tennis ball.

The front limbs attach to the spine through the shoulder girdle, which is unique because it’s not fused to the ribcage like in humans. This loose attachment gives dogs incredible shoulder mobility—they can reach forward and backward in ways we can’t, which is why they excel at digging.

Each front limb contains the humerus (upper arm bone), radius and ulna (forearm bones), carpal bones (wrist), metacarpal bones (palm), and phalanges (toes). The rear limbs have the femur (thighbone), tibia and fibula (shin bones), tarsal bones (ankle), metatarsal bones (foot), and phalanges.

The paws themselves are engineering marvels. Dogs have specialized paw pads that work in conjunction with their skeletal structure to provide traction, shock absorption, and sensory feedback. The bones in the paws are small and delicate, which is why paw injuries are common and often require veterinary attention.

The pelvis in dogs is narrower and more elongated than in humans, designed for speed rather than bipedal stability. This shape affects how dogs move and why certain breeds (like those with hip dysplasia) struggle with rear limb stability.

Joint structure varies by breed. Sporting dogs like Retrievers have loose joints for flexibility, while herding dogs like Border Collies have tighter joints for precision movement. Understanding your dog’s breed-specific skeletal design helps you anticipate potential issues and provide appropriate exercise.

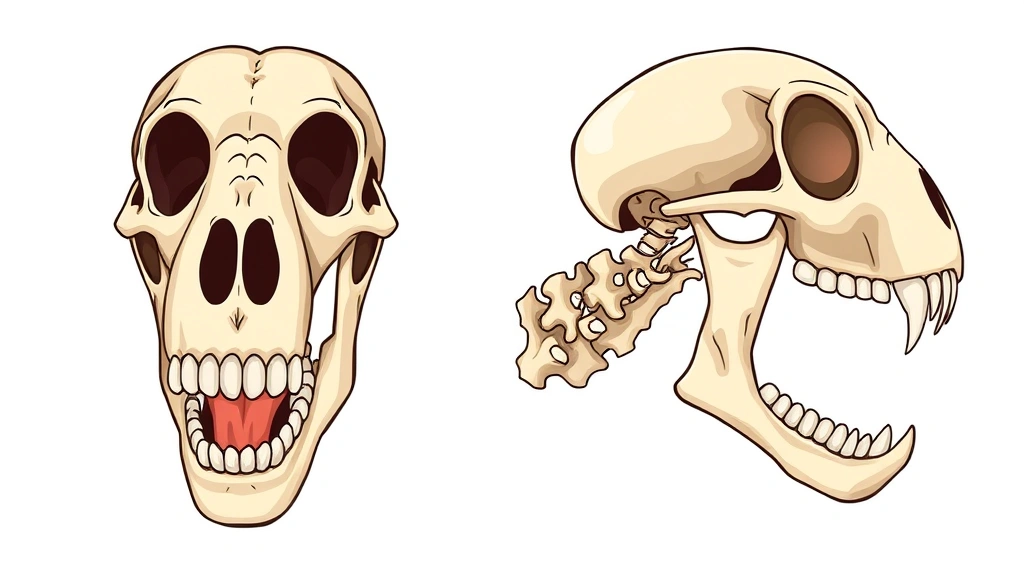

The Skull and Teeth: More Than Just a Pretty Face

The dog skull is proportionally larger and more complex than the human skull, with about 50 bones fused together to create a strong, lightweight structure. The shape varies dramatically by breed—compare a Pug’s flat skull to a Collie’s long, narrow one. These differences aren’t just cosmetic; they affect breathing, bite force, and susceptibility to certain conditions.

The canine teeth (the pointed ones) are the most powerful part of the bite, designed for gripping and tearing. The molars are flat and designed for grinding. The dog skeleton’s jaw structure gives them a bite force of 200-330 pounds per square inch, depending on breed and size. That’s why you should never stick your hand between a dog’s jaws during a fight—the skeletal structure supports immense crushing power.

Puppies are born with deciduous (baby) teeth that fall out around 3-5 months old, replaced by adult teeth. By the time a dog is fully grown, they have 42 permanent teeth compared to our 32. Dental health is directly tied to skeletal health—infections at the tooth root can spread to the jaw bone.

The skull also houses the brain, inner ear, and eyes, all protected by bone. The zygomatic arch (cheekbone) provides attachment points for powerful jaw muscles. The sagittal crest (a ridge running along the top of the skull) is more pronounced in larger dogs and provides additional muscle attachment.

Brachycephalic breeds (flat-faced dogs like Bulldogs and Pugs) have skulls that are compressed, which affects their entire dog skeleton’s biomechanics. These breeds often experience breathing difficulties because their skeletal structure doesn’t allow adequate airway space.

Growth and Development: From Puppy to Adult

A puppy’s skeleton is mostly cartilage at birth, gradually ossifying (turning into bone) over months. This process isn’t complete until 12-18 months for small breeds and up to 24 months for giant breeds. During this time, the dog skeleton is vulnerable to injury and improper development.

Growth plates (epiphyseal plates) are the areas where bones grow in length. These are soft and easily damaged by trauma or excessive exercise. This is why veterinarians recommend limiting jumping and intense running in puppies—you’re not just risking an acute injury; you’re risking permanent skeletal deformities.

Large breed puppies are particularly vulnerable because they grow so rapidly. Their bones are elongating quickly, and the muscles and ligaments are struggling to keep up. This is why large breed puppies need a carefully balanced diet with appropriate calcium and phosphorus ratios. Too much calcium can actually accelerate growth in an unhealthy way, leading to developmental orthopedic disease.

By the time your puppy reaches skeletal maturity, their dog skeleton has adapted to their lifestyle. If they’ve been exercised appropriately and fed well, their bones should be strong and healthy. If they’ve been over-exercised or malnourished, they may have permanent weaknesses.

Senior dogs experience skeletal changes as they age. Bone density decreases, cartilage degenerates, and arthritis becomes more common. The dog skeleton that once allowed your pup to leap onto the couch now creaks a little when they get up in the morning.

Pro Tip: Feed large-breed puppies a large-breed specific puppy food formulated with appropriate calcium and phosphorus levels. Standard puppy foods can lead to developmental orthopedic disease in giant breeds.

Common Skeletal Issues and Health Concerns

Understanding the dog skeleton helps you recognize when something’s wrong. Here are the most common skeletal issues:

- Hip Dysplasia: The femoral head doesn’t fit properly into the hip socket, causing arthritis and pain. German Shepherds, Labrador Retrievers, and other large breeds are predisposed. The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) provides screening and certification for hip dysplasia.

- Elbow Dysplasia: Similar to hip dysplasia but affects the elbow joint. Often causes lameness in the front legs.

- Patellar Luxation: The kneecap slides out of its groove. Common in small breeds and can range from occasional slipping to permanent dislocation.

- Intervertebral Disc Disease (IVDD): Discs in the spine degenerate or rupture, causing pain, weakness, or paralysis. Dachshunds, Basset Hounds, and Corgis are at highest risk due to their long spines.

- Osteochondrosis Dissecans (OCD): A developmental problem where cartilage fails to ossify properly, usually in the shoulder, elbow, or stifle (knee) joint.

- Arthritis: The most common skeletal condition in senior dogs. Degenerative joint disease causes pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility.

- Fractures: Broken bones are common from trauma, falls, or being hit by cars. Some dogs are prone to pathological fractures due to bone disease.

Many of these conditions have genetic components, which is why responsible breeders screen the dog skeleton of their breeding stock. If you’re getting a puppy, ask about health certifications from the American Kennel Club (AKC) or OFA.

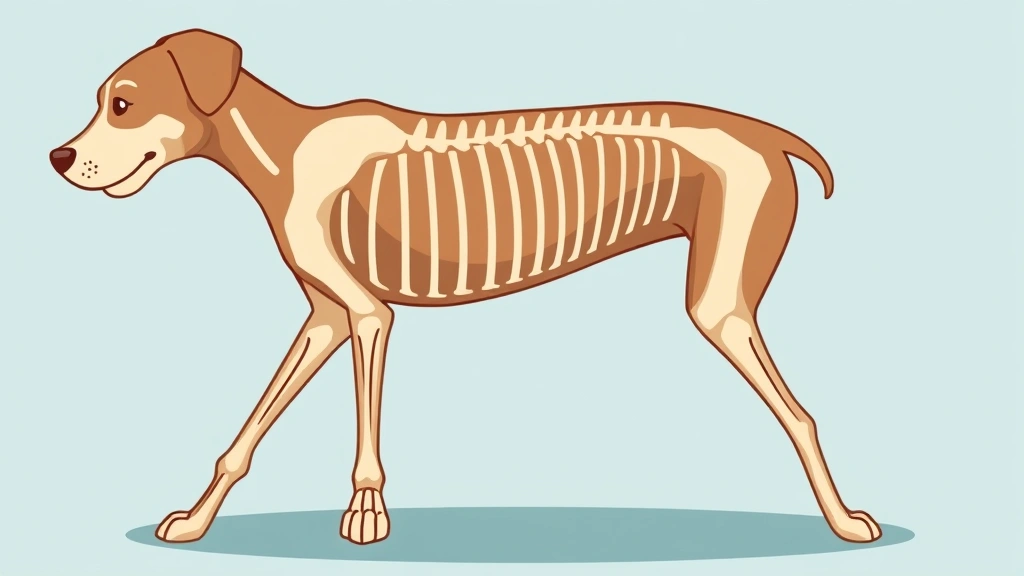

Environmental factors also play a huge role. Excessive jumping, repetitive impact, obesity, and poor nutrition can all accelerate skeletal problems. A dog that’s overweight puts extra stress on their joints, which is why maintaining a healthy weight is crucial for skeletal health.

Caring for Your Dog’s Bones and Joints

Keeping your dog’s skeleton healthy requires a multi-pronged approach. Here’s what actually works:

- Appropriate Exercise: Regular, moderate exercise (like daily walks and play) strengthens bones and maintains joint health. Avoid repetitive high-impact activities like constant jumping or running on hard surfaces.

- Proper Nutrition: Feed a high-quality diet with appropriate levels of calcium, phosphorus, and other minerals. Puppies especially need species-appropriate nutrition. Discuss breed-specific dietary needs with your veterinarian.

- Weight Management: Obesity puts enormous stress on the dog skeleton. If your dog is overweight, work with your vet to develop a weight loss plan. Even a 10% reduction in weight can significantly reduce joint pain.

- Joint Supplements: Glucosamine, chondroitin, and omega-3 fatty acids may help support joint health, especially in senior dogs. Evidence is mixed, but many veterinarians recommend them for dogs with arthritis.

- Orthopedic Support: Orthopedic beds, ramps, and stairs reduce impact on the skeleton. These are especially important for senior dogs and breeds prone to skeletal issues.

- Regular Veterinary Checkups: Your vet can detect early signs of skeletal problems before they become serious. X-rays can reveal arthritis, dysplasia, and other issues.

- Avoid Extreme Temperatures: Cold weather can exacerbate arthritis pain. Keep your senior dog warm and comfortable during winter.

- Controlled Swimming: Swimming is excellent low-impact exercise for the dog skeleton. It builds muscle without stressing joints.

If your dog has a known skeletal condition like hip dysplasia or IVDD, ask your vet about management strategies and when to consider surgical intervention. Some conditions are manageable with conservative treatment (medication, physical therapy, weight management), while others may require surgery.

Physical therapy is increasingly recognized as important for skeletal health. A certified canine rehabilitation therapist can design exercises that strengthen the muscles supporting the skeleton, which reduces stress on joints and bones.

For dogs with arthritis, pain management is crucial. This might include NSAIDs, joint injections, laser therapy, or acupuncture. The goal is to keep your dog comfortable and mobile, which actually helps preserve skeletal function better than complete rest.

Pro Tip: Consider pet insurance that covers orthopedic conditions. Skeletal surgeries can be expensive, and having coverage gives you more options if your dog needs intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many bones does a dog have?

– Dogs have approximately 319 bones, compared to 206 in humans. The exact number varies slightly by breed and individual, and some sources cite 320 bones. The extra bones are primarily in the spine and tail, giving dogs their characteristic flexibility.

Why do puppies have softer bones than adult dogs?

– Puppy bones are mostly cartilage, which is softer and more flexible than bone. Over 12-24 months (depending on breed), this cartilage gradually ossifies (hardens) into bone. This process is why puppies are more vulnerable to skeletal injuries and why growth plates need protection during development.

Can a dog’s broken bone heal on its own?

– Some minor fractures may heal with rest, but most broken bones require veterinary treatment. Without proper alignment and stabilization, bones can heal incorrectly, leading to permanent lameness or deformity. Get any suspected fracture evaluated by a vet immediately.

What’s the difference between a dog’s skeleton and a human skeleton?

– Dogs have more bones, a more flexible spine, and limbs designed for quadrupedal movement. Dogs are digitigrade (walk on toes) while humans are plantigrade (walk flat-footed). Dogs also have a much more powerful bite force due to their skeletal jaw structure.

Is it bad for dogs to go up and down stairs?

– Occasional stair use is fine, but repetitive stair climbing can stress the dog skeleton, especially in puppies, senior dogs, and breeds prone to joint problems. Use ramps or stairs with support for dogs with mobility issues.

Can diet affect my dog’s skeletal health?

– Absolutely. Proper nutrition is essential for bone development and maintenance. Puppies need appropriate calcium and phosphorus ratios. Adult dogs benefit from balanced nutrition with adequate protein and minerals. Senior dogs may benefit from joint-supporting supplements.

What breed of dog has the most skeletal problems?

– Large and giant breeds are prone to hip and elbow dysplasia. Dachshunds and other long-backed breeds are prone to IVDD. Brachycephalic breeds have skeletal abnormalities affecting breathing. Small breeds are prone to patellar luxation. Essentially, every breed has predispositions based on their skeletal structure.

How can I tell if my dog has a skeletal problem?

– Signs include limping, reluctance to jump or climb stairs, stiffness (especially after rest), difficulty getting up, whimpering during movement, and swelling around joints. Any of these warrant a veterinary evaluation.

Is arthritis inevitable in senior dogs?

– Arthritis is common but not inevitable. Maintaining a healthy weight, providing appropriate exercise, and supporting joint health throughout your dog’s life can significantly reduce arthritis severity. Some dogs reach old age with minimal joint problems.

When should I start worrying about my puppy’s skeletal development?

– Start from day one. Avoid excessive jumping and running until growth plates close (12-18 months for small breeds, up to 24 months for giant breeds). Feed appropriate puppy nutrition and avoid overfeeding, which accelerates growth abnormally.