How Strong Is a Dog’s Detoxification System? What Every Pet Owner Should Know

Your dog’s body is a remarkable machine, constantly working behind the scenes to keep them healthy and thriving. One of the most fascinating—and often misunderstood—systems is their detoxification process. Unlike humans, dogs have evolved with some impressive natural defenses against toxins, but their detox abilities aren’t quite what many pet owners assume. The truth? Dogs are simultaneously tougher and more vulnerable than we think, depending on what toxin we’re talking about.

Understanding how strong your dog’s detoxification system really is can mean the difference between a minor scare and a serious health crisis. Whether your pup has gotten into something questionable at the park or you’re wondering if that plant in your living room poses a real threat, it’s crucial to know what your furry friend’s body can and cannot handle. Let’s dig into the science behind canine detoxification and explore what makes some dogs seemingly immune to things that would make others seriously ill.

The reality is that your dog’s detox system is both more capable and more limited than you might expect—and knowing the difference could save your pet’s life.

How Dogs’ Detoxification Systems Work

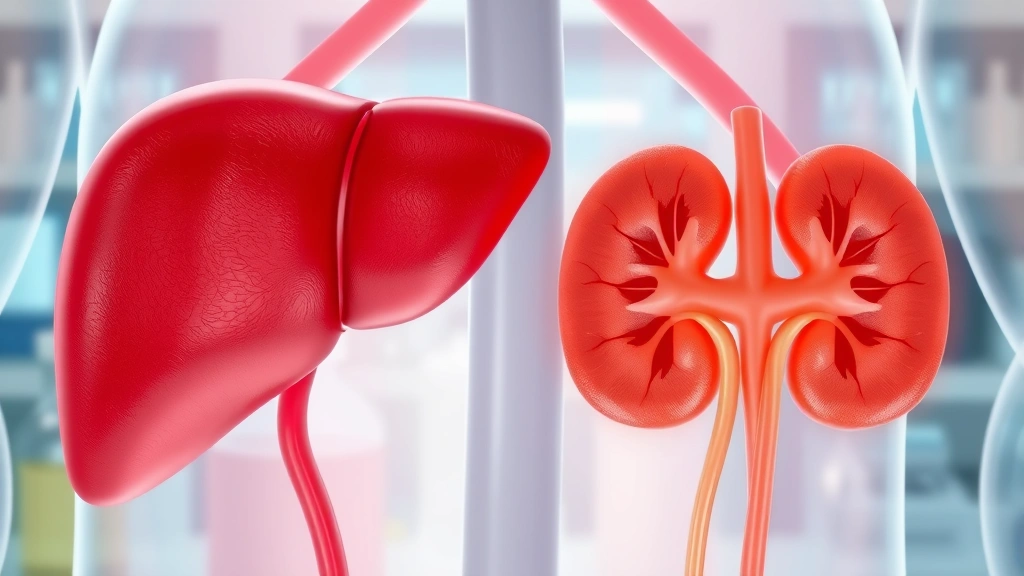

When we talk about detoxification, we’re really discussing the body’s ability to process and eliminate harmful substances. Dogs have a multi-layered system designed to recognize foreign compounds, neutralize them, and eliminate them through urine, feces, or bile. This system involves several organs working in concert, primarily the liver, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.

The process begins the moment a toxin enters your dog’s body, whether through ingestion, inhalation, or absorption through the skin. Their digestive system acts as the first line of defense, breaking down food and other substances. Specialized enzymes in the stomach and intestines begin the initial breakdown process. Some toxic compounds are eliminated right here—they never make it past the gut barrier.

However, the truly impressive work happens at the cellular level. Your dog’s liver contains multiple enzyme systems, collectively known as the cytochrome P450 system, that transform toxins into less harmful compounds. This process, called biotransformation, changes the chemical structure of toxins to make them water-soluble so they can be filtered out through the kidneys and excreted in urine.

What makes this system so interesting is that it’s not one-size-fits-all. Different dogs metabolize different substances at wildly different rates, which explains why one dog might shrug off something that would devastate another. Age, genetics, overall health, and even diet all influence how efficiently this system operates.

The Liver and Kidneys: Your Dog’s Detox Powerhouses

If your dog’s body were a factory, the liver would be the processing plant and the kidneys would be the quality control department. These two organs handle the heavy lifting when it comes to detoxification, and understanding their roles helps explain why some toxins are more dangerous than others.

The Liver’s Critical Role

Your dog’s liver is an absolute powerhouse. This organ performs over 500 different functions, and detoxification is just one of them. The liver filters blood coming from the digestive tract before it circulates to the rest of the body. This gives it first crack at neutralizing anything potentially harmful.

The liver accomplishes detoxification through three main phases. Phase I involves oxidation and reduction reactions that break down toxins. Phase II adds water-soluble compounds to toxins, making them easier to excrete. Phase III involves transporters that move these processed toxins out of liver cells for elimination. It’s an elegant system, but it has limits—and when toxins overwhelm the liver, serious problems develop quickly.

This is why dogs can develop liver disease from chronic exposure to toxins or from acute poisoning events. The liver can regenerate itself remarkably well, but only if it’s not damaged beyond repair.

Kidney Function in Toxin Elimination

While the liver transforms toxins, the kidneys act as the body’s filtration system. These bean-shaped organs filter waste products from the blood and concentrate them into urine for excretion. The kidneys are particularly important for eliminating water-soluble toxins that the liver has already processed.

The glomeruli, tiny filtering units within each kidney, work tirelessly to separate waste from useful compounds. However, certain toxins can damage the kidney tubules directly, which is why some poisons are particularly dangerous. If the kidneys become compromised, the entire detoxification system backs up, and toxins accumulate in the bloodstream.

Understanding the Limits of Canine Detoxification

Here’s where things get sobering: your dog’s detoxification system, while impressive, has definite limits. It evolved to handle natural toxins found in their ancestral environment—not the pharmaceutical compounds, pesticides, and industrial chemicals they encounter in modern life.

One critical difference between dogs and humans is metabolic capacity. Dogs lack certain enzymes that humans possess, which means they cannot efficiently process some compounds that we handle relatively easily. Conversely, dogs have enzymatic capabilities that exceed ours in some areas, making them actually more resistant to certain toxins. This inconsistency is why chocolate, grapes, and xylitol are toxic to dogs but not to people.

The dose also matters enormously. A dog’s detoxification system can handle small amounts of many harmful substances, but there’s always a threshold. Once the liver becomes saturated with toxins and cannot process them fast enough, they accumulate in the blood and tissues, causing acute poisoning. This is why a small amount of onion might cause no visible problems, while a large quantity can trigger hemolytic anemia.

Additionally, the liver can only process one toxin at a time, roughly speaking. When a dog is exposed to multiple toxins simultaneously, the system becomes overwhelmed much more quickly. A dog that might survive moderate exposure to one poison could succumb to a combination of lesser toxins.

Common Toxins Dogs Handle Better Than Humans

Dogs are surprisingly resilient to certain substances that would cause serious harm to people. Understanding what dogs can tolerate helps put the risks in perspective—though “can tolerate” doesn’t mean “should be exposed to.”

Bacterial Endotoxins

One reason dogs can eat poop without becoming seriously ill as often as you’d expect relates to their impressive resistance to bacterial endotoxins. These toxins, produced by gram-negative bacteria, are far less likely to cause severe illness in dogs compared to humans. Their gut flora and stomach acid are particularly efficient at neutralizing these compounds.

Certain Plant Alkaloids

Many plants produce alkaloid compounds as natural defenses against herbivores. Dogs can metabolize some of these alkaloids more efficiently than humans can. However, this doesn’t make plants like poison ivy safe for dogs—they can still cause significant reactions, just through different mechanisms.

Aflatoxins and Mycotoxins

Dogs have decent resistance to certain molds and their toxins compared to other species, though they’re not immune. Their liver enzymes can process some mycotoxins relatively efficiently, which is why dogs eating slightly moldy food sometimes escape without serious consequences.

Toxins That Overwhelm a Dog’s System

While dogs have impressive detox abilities in some areas, other toxins bypass their defenses almost entirely. These substances either directly damage organs or overwhelm the detoxification system so quickly that the dog’s body cannot cope.

Chocolate and Theobromine

Chocolate is the classic example of a substance dogs cannot metabolize effectively. Dogs lack sufficient enzymes to break down theobromine efficiently, so it accumulates in their system. If your dog eats chocolate, the theobromine can reach toxic levels in their bloodstream, affecting the heart and nervous system. Dark chocolate and baking chocolate are particularly dangerous because they contain higher concentrations of theobromine.

Xylitol

This artificial sweetener represents a modern toxin that dogs’ ancient detoxification systems never evolved to handle. Xylitol triggers a massive insulin release in dogs, causing dangerous hypoglycemia. The liver cannot neutralize this effect, making xylitol one of the most rapidly dangerous toxins for dogs.

Certain Heavy Metals

Lead, mercury, and other heavy metals can accumulate in dogs’ tissues faster than their detoxification system can eliminate them. Unlike some toxins that the liver can transform and the kidneys can filter, heavy metals often require chelation therapy—the body cannot process them through normal detoxification pathways.

Specific Medications and Drugs

Acetaminophen, NSAIDs like ibuprofen, and certain other human medications are particularly dangerous for dogs because their liver enzymes cannot metabolize them safely. What’s a safe dose for a human can be toxic or even lethal for a dog.

Toxins That Cause Neurological Damage

Some toxins, like certain pesticides and toxins that cause seizures in dogs, work by disrupting neurological function directly. The detoxification system cannot prevent this damage once the toxin reaches the brain. These require immediate veterinary intervention to prevent catastrophic harm.

Breed and Individual Differences in Detox Abilities

Not all dogs are created equal when it comes to detoxification. Significant variations exist between breeds and even between individual dogs of the same breed, and these differences can be literally lifesaving.

Genetic Variations in Enzyme Production

Some dog breeds have genetic variations that affect how efficiently their liver produces detoxification enzymes. Certain breeds may have higher or lower levels of specific cytochrome P450 enzymes, making them more or less susceptible to particular toxins. This is partly why some dogs seem to have cast-iron stomachs while their littermates are prone to poisoning.

Age-Related Changes

Puppies have immature liver enzyme systems and cannot detoxify many substances effectively. Senior dogs often have declining liver and kidney function, reducing their detoxification capacity. Middle-aged dogs generally have the most robust detoxification abilities. This is why the same substance might cause minimal problems in a 3-year-old dog but serious illness in a puppy or senior.

Health Status and Medications

Dogs with existing liver or kidney disease have severely compromised detoxification abilities. Similarly, dogs taking certain medications may have reduced enzyme activity, making them more susceptible to toxins. A dog on antibiotics, for example, might metabolize other substances differently than usual.

Individual Metabolic Differences

Just as humans have different metabolic rates, individual dogs process toxins at different speeds. Genetics, body composition, and overall health status all influence how quickly a dog’s liver can neutralize a particular poison. This is why two dogs exposed to the same toxin might have vastly different outcomes.

How to Support Your Dog’s Natural Detoxification

While you cannot make your dog’s detoxification system stronger through supplements or diet alone, you can certainly support optimal function. A healthy liver and kidney system is better equipped to handle whatever comes its way.

Provide Quality Nutrition

The liver requires specific nutrients to produce detoxification enzymes. Adequate protein, B vitamins, and minerals like zinc and selenium are essential. High-quality dog food formulated to meet AAFCO standards provides these nutrients in appropriate quantities. Avoid cheap fillers and artificial additives that might add to your dog’s detoxification burden.

Maintain Appropriate Weight

Obesity stresses the liver and impairs its function. Keeping your dog at a healthy weight reduces the workload on their detoxification system and helps maintain overall metabolic health. This alone can significantly improve how well their body handles toxins.

Ensure Adequate Hydration

Water is essential for kidney function and toxin elimination through urine. Dogs that don’t drink enough water cannot efficiently filter toxins from their blood. Ensure your dog always has access to fresh, clean water.

Regular Veterinary Checkups

Routine bloodwork can catch liver and kidney problems before they become serious. If your dog has any underlying organ dysfunction, your veterinarian can adjust their care accordingly and warn you about particular toxin risks.

Minimize Unnecessary Toxin Exposure

This is perhaps the most important step. Keep pesticides, chemicals, medications, and toxic plants away from your dog. Don’t assume their detoxification system will handle something just because they’re a dog. Remember, knowing when to induce vomiting in dogs is important emergency knowledge, but prevention is always better than treatment.

Avoid “Detox” Products

Many commercial “detox” supplements for dogs lack scientific evidence and can actually stress the liver further. Your dog’s detoxification system works best when you simply provide good nutrition and avoid unnecessary toxins. If your dog has been poisoned, work with a veterinarian—not with unproven supplements.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a dog’s detoxification system stronger than a human’s?

It’s not straightforward—dogs are stronger in some areas and weaker in others. Dogs can handle some bacterial toxins better than humans, but they’re much more vulnerable to compounds like chocolate, xylitol, and acetaminophen. The real difference is that dogs’ detoxification systems evolved for a different environment than the modern world they now inhabit.

Can I give my dog supplements to boost detoxification?

Most commercial detox supplements lack scientific evidence of effectiveness and can actually stress the liver. Focus instead on providing quality nutrition, maintaining healthy weight, and ensuring adequate hydration. If you’re concerned about your dog’s liver or kidney function, consult your veterinarian about specific nutrients or supplements that might be appropriate for your individual dog.

How long does it take for a dog’s body to eliminate a toxin?

This varies dramatically depending on the toxin, your dog’s size, age, and overall health. Some toxins are eliminated within hours, while others accumulate in tissue and take weeks or months to clear. Liver damage can be permanent if the dose was high enough. This is why immediate veterinary care is critical for suspected poisoning.

Are some dog breeds more resistant to toxins?

Yes, genetic variations between breeds can affect enzyme production and detoxification efficiency. However, individual variation within breeds is often greater than variation between breeds. Age, health status, and current medications matter more than breed in most cases.

What should I do if I think my dog has been poisoned?

Contact your veterinarian or the ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center immediately at (888) 426-4435. Time is critical with many toxins. Do not try home remedies or wait to see if symptoms develop. Prompt professional treatment can mean the difference between recovery and serious harm.

Can activated charcoal help my dog detoxify?

Activated charcoal can be helpful in certain poisoning situations if given very soon after ingestion—it binds to some toxins in the stomach before they’re absorbed. However, it’s not effective for all toxins and can actually interfere with medications. Only use it under veterinary guidance.